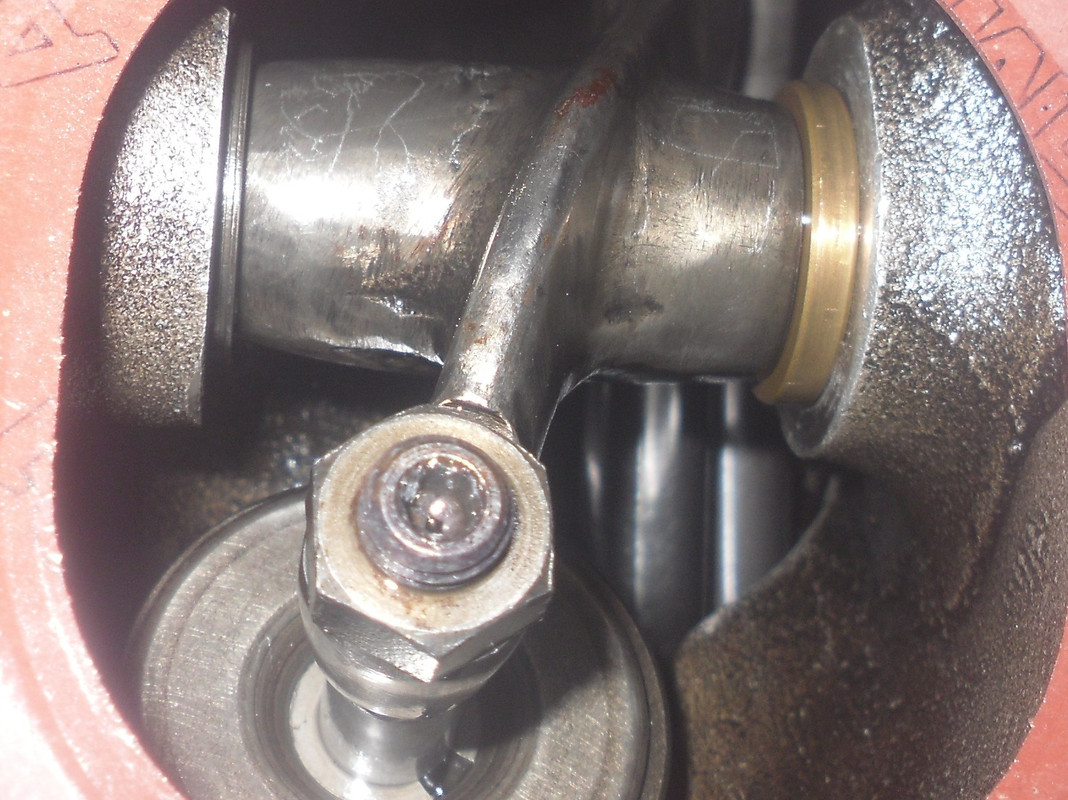

Just got my head serviced with new valves, guides and springs. All rockers had the spring/shim. One had 3 washer shims, the rest had one. Doesn't look right to me. What are thoughts on using, vs eliminating the spring/shims and just using just solid shim washers? What should the end clearance be, and should the rocker be centered over the valve stem? Any other information about installing the rockers is welcome.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Rocker arm shimming clearance question

- Thread starter fid04

- Start date

seattle##gs

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Oct 28, 2014

- Messages

- 2,165

The reason I like the stock Thackeray spring set up is that it makes it easier to assemble the head especially when it's 200 or more degrees. I assemble it cold with an undersize spindle.

Fiddling with spacers and shims gives the opportunity to align the rocker tip to the valve stem but it would be a lot of work for maybe a minute gain. Count me out.

Fiddling with spacers and shims gives the opportunity to align the rocker tip to the valve stem but it would be a lot of work for maybe a minute gain. Count me out.

Britstuff

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jan 8, 2021

- Messages

- 190

I am running solid shim washers on my Commando. I used to have them on my Dominator, but I have had the head apart a few times in the last few years, and like seattle##gs says, they are a bit of a pain to align and install, so I decided to go back to Thackery washers. Initial install takes time and patience, each shim has to be ground down to size. I probably spent an hour or more on each one, grinding them to size by hand with a high quality fine grinding stone.

I do not notice any difference is noise. I think there is probably a slight reduction in friction with the solid shims. If you have the time and patience I don't think there is any overarching reason not to use them?

I do not notice any difference is noise. I think there is probably a slight reduction in friction with the solid shims. If you have the time and patience I don't think there is any overarching reason not to use them?

Last edited:

marshg246

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2015

- Messages

- 5,873

I wish you were a Premier Member so I could PM you as I really don't need the feedback that will likely come from this:Just got my head serviced with new valves, guides and springs. All rockers had the spring/shim. One had 3 washer shims, the rest had one. Doesn't look right to me. What are thoughts on using, vs eliminating the spring/shims and just using just solid shim washers? What should the end clearance be, and should the rocker be centered over the valve stem? Any other information about installing the rockers is welcome.

The thin flat washer goes on the outside of each rocker. Unless someone has modified the rockers, there must be only one.

The spring goes on the inside of the rocker by itself.

The adjuster is NOT supposed to be centered on the valve stem. If very far off, suspect that someone before you has "fixed" the rocker.

A very famous race engine builder likes the adjuster dead center on the valve stem and no spring washer. He grinds the rockers and adds flat washers as needed to make that happen. I obviously disagree.

Some here also don't like the spring washers and have other solutions. I obviously disagree.

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2004

- Messages

- 21,132

Several members disagree with this, myself included.The adjuster is NOT supposed to be centered on the valve stem.

Post in thread 'Thrust washers on rocker shaft' https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/thrust-washers-on-rocker-shaft.40994/post-700237

marshg246

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2015

- Messages

- 5,873

No kidding, as I predicted!Several members disagree with this, myself included.

Post in thread 'Thrust washers on rocker shaft' https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/thrust-washers-on-rocker-shaft.40994/post-700237

In truth, there's really not much anyone can say here that someone here doesn't disagree with! Just like all the disagreements in the thread you presented!

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2004

- Messages

- 21,132

Post in thread 'Valve Rotators' https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/valve-rotators.26713/post-400882

Shelby-Right

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jan 28, 2022

- Messages

- 905

General end float, for crankshafts, camshafts in cars . 002"-.006". I'd say 4-5 thou would be fine, if you go that way. I had to file some oil grooves into mine, to help lube my exhaust valve, but that was an old BSA b33, not many original parts on the inside

. Cheers

. Cheers

Seems to be different schools of thought on the subject. Curious if you have ever put any kind of reference mark on the side of the valve stem to test out your theory and see if they do indeed turn.I wish you were a Premier Member so I could PM you as I really don't need the feedback that will likely come from this:

The thin flat washer goes on the outside of each rocker. Unless someone has modified the rockers, there must be only one.

The spring goes on the inside of the rocker by itself.

The adjuster is NOT supposed to be centered on the valve stem. If very far off, suspect that someone before you has "fixed" the rocker.

A very famous race engine builder likes the adjuster dead center on the valve stem and no spring washer. He grinds the rockers and adds flat washers as needed to make that happen. I obviously disagree.

Some here also don't like the spring washers and have other solutions. I obviously disagree.

Fast Eddie

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Oct 4, 2013

- Messages

- 22,718

Way back, in Comnoz’ fabulous ‘spintron’ thread, he suggested that the Thackeray washers probably provide a small damping effect to the rocker which would be beneficial for valve control, especially at higher rpms.

marshg246

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2015

- Messages

- 5,873

You can look at the wear pattern on the valve stem and see that they do.Seems to be different schools of thought on the subject. Curious if you have ever put any kind of reference mark on the side of the valve stem to test out your theory and see if they do indeed turn.

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2004

- Messages

- 21,132

I have only seen the top of used valve stems with one straight line scratch marks caused by the valve adjuster contact. There is no way for a valve to turn and there is no evidence that I have seen that they do. I like to see nicely centered valve stem to adjuster contact. And use bronze spacers instead of the Spring "washer" as they call it in the parts book. And different thickness "thrust" washers to get minimum end play. They can be had in 15 and 30 thou.BTW, IMHO, centering the rocker is bad - the valve is supposed to turn.

https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/thrust-washers-on-rocker-shaft.40994/post-700245

"I just looked at maybe 20 old valves, and they all have linear wear marks.

They did not rotate."

- Joined

- Feb 10, 2009

- Messages

- 3,180

I don’t believe replacing spring washers with shims, on a rocker shaft make a Commando go faster. It just seems like a “racing” thing to do.

I’m not clever enough to pass a judgment on centre or off-centre valve tip contact.

I’m not clever enough to pass a judgment on centre or off-centre valve tip contact.

cliffa

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- May 26, 2013

- Messages

- 4,438

An interesting point in the two videos that @baz posted in that thread, is that the valves springs and caps, (so presumably the valves as well), appear to be rotating even when the valves are closed, in which case it makes no difference where the rocker contacts the valve tip.I have only seen the top of used valve stems with one straight line scratch marks caused by the valve adjuster contact. There is no way for a valve to turn and there is no evidence that I have seen that they do. I like to see nicely centered valve stem to adjuster contact. And use bronze spacers instead of the Spring "washer" as they call it in the parts book. And different thickness "thrust" washers to get minimum end play. They can be had in 15 and 30 thou.BTW, IMHO, centering the rocker is bad - the valve is supposed to turn.

https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/thrust-washers-on-rocker-shaft.40994/post-700245

"I just looked at maybe 20 old valves, and they all have linear wear marks.

They did not rotate."

- Joined

- Aug 30, 2006

- Messages

- 845

Setting the rockers with a precise amount of offset is time consuming. It is unlikely they did it at the factory, and IF they did, and felt it was important, it would have been mentioned in the workshop manual.

Surely some must have left the factory off center, but it certainly wasn't intentional.

Greg seems to think it's important, so we must assume he adjusts each rocker individually. Shimming only works one way. The other direction requires machining the rocker.

So Greg, enlighten us how you machine the rockers, or do you just bend them ?

Surely some must have left the factory off center, but it certainly wasn't intentional.

Greg seems to think it's important, so we must assume he adjusts each rocker individually. Shimming only works one way. The other direction requires machining the rocker.

So Greg, enlighten us how you machine the rockers, or do you just bend them ?

Last edited:

marshg246

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2015

- Messages

- 5,873

AFAIK, no one is talking about valve rotators here - that's completely different tech as are valve springs designed to turn valves.Post in thread 'Valve Rotators' https://www.accessnorton.com/NortonCommando/valve-rotators.26713/post-400882

- Joined

- Nov 20, 2004

- Messages

- 21,132

Exactly.AFAIK, no one is talking about valve rotators here - that's completely different tech as are valve springs designed to turn valves.

"A valve will turn a tiny bit each time the valve opens due to the twist imparted by the compressing of the spring. If there is sufficient friction [ie no rotator provisions] then the valve will turn back to it's original position as the spring returns to the seated position."

marshg246

VIP MEMBER

- Joined

- Jul 12, 2015

- Messages

- 5,873

How Vintage British Engines Achieved Valve Rotation

Below is a clean, subsystem‑level breakdown of how the major marques handled it. Norton (Singles & Twins)

Norton (Singles & Twins)

Norton relied almost entirely on passive rotation caused by:- Off‑center rocker pad contact

- Asymmetric rocker geometry

- Valve spring wind‑up and release

- Slight guide clearance

- Seat impact forces

Why Norton didn’t need rotators

Norton’s rocker arms — especially on the Dominator and Commando — have a naturally offset pad sweep. This offset is baked into the rocker spindle geometry and produces consistent slow rotation without extra hardware.Norton’s exhaust valves typically show:

- A slow, steady rotation pattern

- Even seat wear

- No swirl marks indicating excessive rotation

Triumph (Pre‑Unit & Unit Twins)

Triumph (Pre‑Unit & Unit Twins)

Triumph also relied on passive rotation, but their rocker geometry is different from Norton’s.Key features:

- Rocker arms are narrower

- Pad sweep is more centered

- Valve stems are longer and more flexible

- Spring wind‑up plays a bigger role

- Spring torsion

- Valve bounce at higher RPM

- Slight rocker offset (less than Norton)

BSA (A‑Series, B‑Series, C‑Series)

BSA (A‑Series, B‑Series, C‑Series)

BSA’s approach is closer to Triumph than Norton.Characteristics:

- Moderate rocker offset

- High spring wind‑up due to long stems

- More guide clearance than Triumph

- Heavier valve gear → more bounce → more rotation

Why None of These Engines Used Rotocaps

Why None of These Engines Used Rotocaps

Rotocaps (spring‑loaded mechanical rotators) were used in:- Heavy‑duty diesels

- Some aircraft engines

- Later automotive engines with high exhaust temps

- They add mass to the valvetrain

- They reduce RPM capability

- They complicate rocker geometry

- They weren’t needed — passive rotation was enough

- Air‑cooled engines already had generous guide clearances

“If the geometry already rotates the valve, don’t add parts.”

Summary Table: How Each Brand Achieved Rotation

Summary Table: How Each Brand Achieved Rotation

| Brand | Rotation Method | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Norton | Strong passive rotation from rocker offset | Most consistent rotation of the group |

| Triumph | Moderate passive rotation from spring torsion + slight offset | Exhaust valves rotate more than intakes |

| BSA | Moderate–strong passive rotation from bounce + guide clearance | High‑RPM singles rotate aggressively |

| AJS/Matchless | Similar to Norton | Rocker geometry naturally off‑center |

| Velocette | Spring torsion dominant | Very smooth rotation, low wear |

Why This Matters for Restoration

Why This Matters for Restoration

When you rebuild these engines today:- If you center the rocker tip perfectly, you may stop valve rotation.

- If you use modern tight guides, you may reduce rotation.

- If you use roller rockers, you may eliminate rotation entirely.

- If you use modern high‑rate springs, rotation may increase.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 211

- Views

- 20,932

- Replies

- 19

- Views

- 3,322

- Replies

- 0

- Views

- 1,539